Hooked on Classics Yet Again: The Face of Cleopatra

Quick: what did Cleopatra look like?

And if the beautiful face that comes most readily to mind is Elizabeth Taylor's from the lumbering

1963 movie extravaganza -- well, until recently it did for me too, and probably would have done so even before Taylor's lamented death last month.

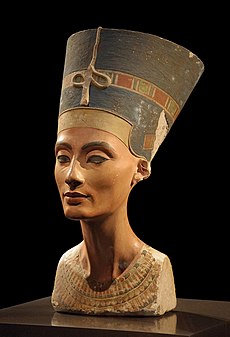

1963 movie extravaganza -- well, until recently it did for me too, and probably would have done so even before Taylor's lamented death last month.With, I'll sheepishly confess, Nefretiri's even more beautiful one a close second in my muddled imagination of the ancient world -- at least until a quick trip to Wikipedia informed me of the little matter of

1300 years intervening between the reigns of the two Egyptian queens.

1300 years intervening between the reigns of the two Egyptian queens.But even taking into account my historical imagination shamelessly in the thrall of pop history and history according to the movies, it turns out to be pretty understandable that I couldn't call an image to mind of a woman whose name has become a byword for fatal female attraction.

Because the

images we have of Cleopatra -- from an age when public representation of rulers was ubiquitous -- are a paltry few, most reliably existing on coins like this one from 36 BC, minted, as Cleopatra's recent biographer, Stacy Schiff, tells us, to announce Antony and Cleopatra's political alliance.

images we have of Cleopatra -- from an age when public representation of rulers was ubiquitous -- are a paltry few, most reliably existing on coins like this one from 36 BC, minted, as Cleopatra's recent biographer, Stacy Schiff, tells us, to announce Antony and Cleopatra's political alliance.Not that there weren't sculptures aplenty all over Egypt during Cleopatra's lifetime (and one in Rome, too: Julius Caesar had it done all in gold, in the temple of Venus that he built) but they haven't survived. For the simple reason that in the years after Antony and Cleopatra's defeat and suicide, as Rome went from Republic to Empire under Octavian (who renamed himself Augustus) her statues were systematically torn down and replaced by those of the conquering Roman emperor. Even as the ancient kingdom of Egypt lost the autonomy under Rome that Cleopatra had worked all her adult life to maintain -- and as, under Augustus, Rome created its own great literature, and a public mythology that outlasted Rome itself by some millenia, with Cleopatra's story transformed into

history's great negative lessons about what happens when a woman gets too much power.

history's great negative lessons about what happens when a woman gets too much power.And if all this leaves little memory of the canny and self-possessed -- if notably unbeautiful -- woman on the coin, with her white diadem of office, a fortune in pearls around her neck and woven through her elaborate hairdo, and her knowing smile, Schiff's recent biography has achieved the job of historical reclamation to spectacular effect. The cover of which book -- at least in its current hardback edition -- manages to have it a number of provocative ways, subtly recalling the image on the coin in its aspect and its handling of the diadem, hair, and pearls, hinting at the fabled beauty we've come to assume even as it rotates the face away from us, turning it backward into shadow.

Particularly artful, that turn into shadow, given how little direct information we have about the woman, Cleopatra VII, who ruled Egypt for twenty-two years -- and how much of what we do "know" comes from a Roman political PR machine staffed by the likes of Virgil, Horace, and Plutarch (who was the main source for Shakespeare).

A family values kind of guy (for his citizenry if not for himself), Augustus clad his empire in a strict ideology of masculinist rectitude. How better to do this than to portray the richest person in the Mediterranean, who spoke nine languages -- a charismatic, profoundly well-educated woman who, in Schiff's words, "knew how to build a fleet, suppress an insurrections, control a currency, alleviate a famine"-- as a sexual wanton who ruled by nefarious wiles? Particularly because that same woman did, after all, sleep with two of the most powerful men of her time, have children with them, and at important junctures, cause both Julius Caesar and Marc Antony to do her bidding.

Cleopatra, as Schiff says, "stood at one of the most dangerous intersections in history, that of women and power." Not to speak, I have to add, of love and sexuality. And while the story we've inherited is sure to dazzle by dint of these sure-fire elements, the actual record is woefully short on specifics. Schiff reminds us that "there is no universal agreement on most of the basic details of her life, no consensus on who her mother was, how long Cleopatra lived in Rome, how often she was pregnant, whether she and Antony married, what transpired at the battle that sealed her fate, [even] how she died."

How then to try to tell the story in its own terms and not those that have shaped our own troubled imaginations of men and women, power and sexuality? Schiff says that she has "not attempted to fill in the blanks." "Mostly," she continues, "I have restored context." Which is an impressively modest way to describe the job she's done of absorbing and marshaling a massive array of historical evidence into a three-hundred page read of... can I say "breathtaking"... liveliness and clarity of style?

"How strange --" my husband said, picking up my copy and reading a page or two, "a biography written in the conditional tense." I hadn't realized it, but he was right. With so much of the record gone forever, one must speculate, make one's best judgments, be imaginative and yet precise in the same paragraph, and not yield an inch of ground when the evidence will allow it.

As in Schiff's impeccably controlled examination of Cleopatra's voyage to Rome. Beginning what's not known ("Whether she traveled for reasons of state or affairs of the heart -- or to introduce Caesar to the infant son he had not yet met -- is unclear") the biographer makes her way to firmer ground and states her case in a meticulous blaze of verbal confidence:

Two things are abundantly clear. She could not have left Egypt were she not firmly in control of the country. And she would not have dared to set foot in Rome had Julius Caesar not wanted her there.A triumph of the conditional, and an inspiration for any journeyperson writer.

I can't recommend this book highly enough, and I'm curious what works of history (particularly in their writing) have thrilled and inspired you in similar ways.

Comments

Post a Comment